"At the beginning of the year 1907," recalled August Blesch, secretary of the Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Company and the president of the Employers’ Association of Detroit (EAD), "the business agents of the various unions were wearing ‘smiles that would not come off,’ and at every opportunity they volunteered the information that in the early spring organized labor was going to put the Employers' Association out of business.”

to put the Employers' Association out of business.”

Indeed, Detroit’s employers confronted a series of strikes that erupted in the spring of 1907. But perhaps no strike ever put the EAD to a greater test than the nine-weeks battle between the members of the EAD’s Brass Division and the local union of metal polishers and buffers.

In 1906, the prolonged struggle between the same union and the Ideal Manufacturing Company nearly precipitated a mass lockout of union workers by the EAD. What was different in 1907 was that the brass industry strike involved more than a dozen companies scattered across the face of the city. This was a far larger and costlier labor battle than the EAD had ever faced. Both sides recognized that the outcome would decide whether organized labor or employers would reign supreme in Detroit.

In April, the union presented its demands. They included a paid 10-minute wash-up time at the end of the workday, the union shop, and a hefty wage increase so that polishers and buffers would each make a minimum of 33 cents per hour (up from 26 and 23 cents per hour, respectively). In dealing with members of the EAD Brass Division the union took the first two demands off the table, but it insisted on a uniform 30 cents per hour minimum wage. The employers, however, would not go higher than 28 cents for polishers and 25 cents for buffers. On April 26, union members voted to strike, and the next day some 500 workers began withholding their services from fourteen EAD brass companies. .jpg?ver=pVeL-SNzegNBl7fD3cfOwQ%3d%3d)

Employers at first let it be known that they would not immediately press to replace their striking employees so as to give them time to reflect on their rash decision to go on strike. But their position hardened during the second week when they warned strikers to return to work within five days or see their jobs permanently go to non-unionists. Both sides dug in for the long haul.

Almost predictably, striking workers and their supporters turned to violence once employers began bringing in new men. Strikebreakers returning home from work found themselves assaulted on the streets and streetcars. Several assailants were arrested, convicted, and paid fines—but most got away. .jpg?ver=mBA8UDLz0CJO4-TAg_aeMQ%3d%3d)

On June 2, the EAD placed a “Notice to the Public” in the local Sunday newspapers that gave its version of the strike’s origins and urged severe penalties for anybody convicted of assault. It then warned that troublemakers would find it very difficult to obtain work in Detroit once the strike was over, “as the Employers’ Association is keeping a close record of all these affairs and furnishing all members with the name of the assaulter, nature of offense committed, penalty imposed, and general character of each case.”

A routine set in by early June as strikers picketed outside the struck shops and police officers escorted strikebreakers to and from work. Time, however, was not on the side of the strikers, and at the beginning of the eighth week they dramatically escalated the conflict.

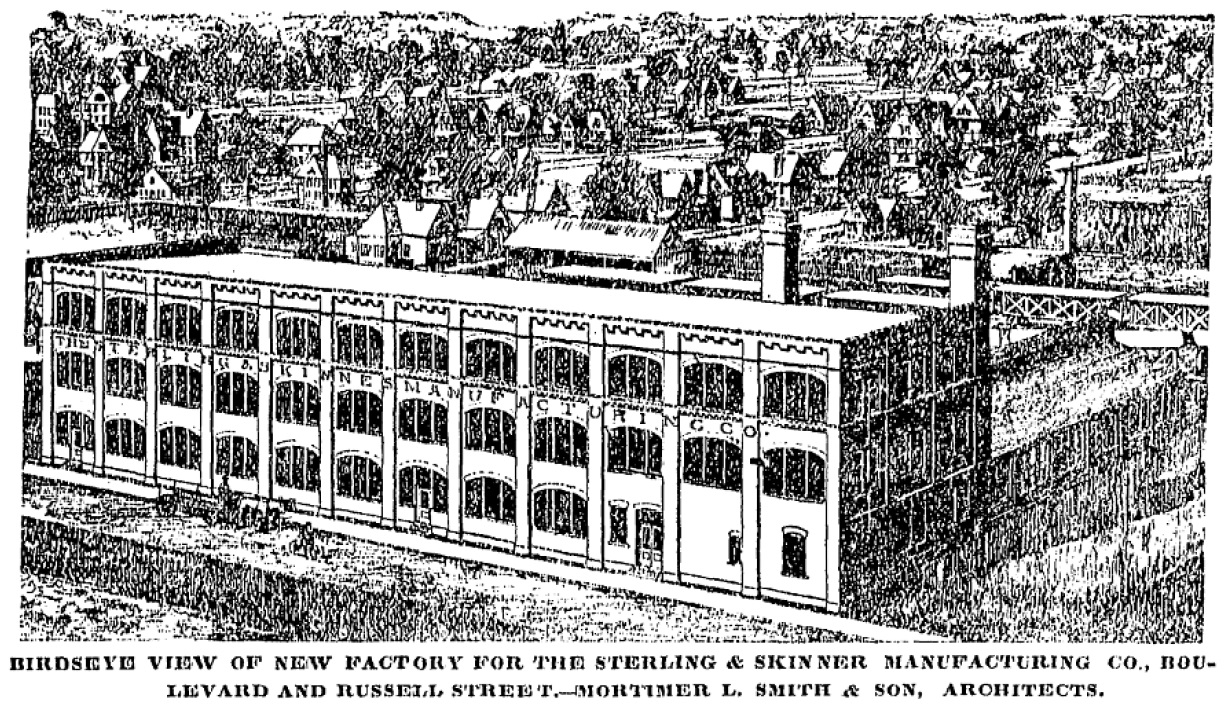

On Saturday, June 15, a crowd of nearly 200 strikers and their allies began gathering before dawn near the plant of Sterling & Skinner Manufacturing Company at East Grand Boulevard and Russell Street. When two dozen Hungarian strikebreakers accompanied by a sixteen-man police squad got close, they let loose with a volley of stones. The crowd withdrew when the officers brandished their revolvers and threatened to open fire, then dispersed into the side streets and the saloons in the area. Biding their time, they reemerged at the noon quitting hour to once again mix it up with strikebreakers and police.

On Saturday, June 15, a crowd of nearly 200 strikers and their allies began gathering before dawn near the plant of Sterling & Skinner Manufacturing Company at East Grand Boulevard and Russell Street. When two dozen Hungarian strikebreakers accompanied by a sixteen-man police squad got close, they let loose with a volley of stones. The crowd withdrew when the officers brandished their revolvers and threatened to open fire, then dispersed into the side streets and the saloons in the area. Biding their time, they reemerged at the noon quitting hour to once again mix it up with strikebreakers and police.

Skirmishes like this took place at most of the brass shops over the next week, but Sterling & Skinner bore the brunt of it. By Tuesday morning, only seven of its replacement workers showed up for work. The others must have been scarred off by Monday evening’s daring and coordinated attack on the Fort Street streetcar carrying twenty-two strikebreakers returning home from work to Delray (the Hungarian section of town in southwest Detroit). .jpg?ver=Jo_C-FcvwUqG_l54me6BxA%3d%3d)

The polishers’ strike forced Sterling & Skinner to close its brass foundry, and when its lathe hands also quit the company considered shutting down the plant altogether. Frederick Skinner, one of the firm’s principal owners, warned that the company might even close for good because Detroit had acquired the name of “the labor trouble city.” “At this very moment,” a frustrated Skinner mused, “there is being waged, between capital and labor, one of the fiercest conflicts in the history of Detroit.” .jpg?ver=vcD9ZXlgSX6Di2Ve_I4Rhg%3d%3d)

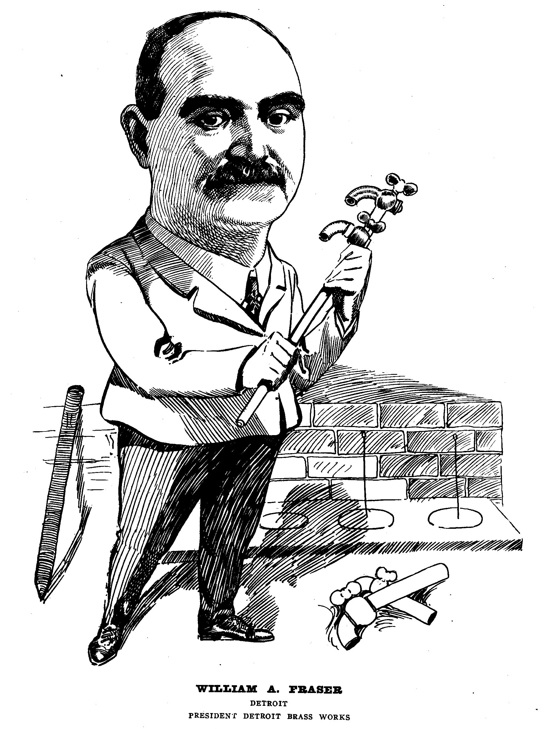

Employers worried about the escalating battles in the streets and exhaustion of the city’s police force. “The situation now borders on anarchism," said William Fraser, president of the Detroit Brass Works and a member of the Executive Board of the EAD. He warned that unless the police and courts took prompt action to suppress disorder, capital would flee Detroit for a safe haven. The local newspapers also condemned the violence. According to Detroit Saturday Night, “the labor question in Detroit is no longer one of wages and hours of work. It is a question of law and order. Shall the police or the mob control the streets of Detroit?” The Commissioner of Police suggested that his men might have to put down their clubs and start using bullets to regain control of the streets.

The EAD’s attorney, George Monaghan, urged Mayor William Thompson to declare an emergency and request the State militia, but was turned down. Undeterred, that same day Monaghan quickly secured a sweeping injunction in Wayne County Circuit Court that prohibited scores of named defendants from boycotting, picketing and patrolling around the struck factories, loitering or congregating in the neighborhood of the plants, or following or speaking to strikebreakers.

The union forces, however, defied the injunction. Not willing to see matters get unalterably out of control, Mayor Thompson attempted to bring the two sides together to secure a resolution of the strike. On the evening of Thursday, June 27, he brought together on the veranda of his Trumbull Avenue house the union’s business agent, Otto Gersabeck, and William Fraser, a close neighbor of the mayor and a leading member of the EAD’s Brass Division. While Fraser insisted that the informal chat was not a conference and that he was not there to represent the EAD, he indicated that he would be happy to pay a 30 cents hourly wage for polishers and buffers and also reinstate his former employees—just as long as it ended the strike without delay.

strike. On the evening of Thursday, June 27, he brought together on the veranda of his Trumbull Avenue house the union’s business agent, Otto Gersabeck, and William Fraser, a close neighbor of the mayor and a leading member of the EAD’s Brass Division. While Fraser insisted that the informal chat was not a conference and that he was not there to represent the EAD, he indicated that he would be happy to pay a 30 cents hourly wage for polishers and buffers and also reinstate his former employees—just as long as it ended the strike without delay.

While having lunch the next day at the Griswold House with three other brass manufacturers who were also eager to see a quick end to the strike, Fraser momentarily excused himself and then returned with Gersabeck. The business agent .jpg?ver=8-UeuN3U3XnKYd8KDiaWOw%3d%3d) liked what he heard during the conversation, and that evening he persuaded union members to vote to end the strike.

liked what he heard during the conversation, and that evening he persuaded union members to vote to end the strike.

Saturday’s newspapers featured news that the long strike was finally over, in part due to secret meetings that left both sides satisfied. Brass manufacturers were surprised and stunned to read the news, for no discussions had been authorized with the union. At a special EAD Brass Division meeting that evening, not one person present admitted to speaking with any union official. Assured that Gersabeck had concocted the story about secret meetings and an agreement, EAD president August Blesch and two others went to the newspapers late on Saturday night to set things right.

.jpg?ver=88v8YyBsUqDb0Rs5HNLpNA%3d%3d) The front-page story in Sunday’s newspapers presented the brass manufacturers’ version of events—that the strikers had surrendered, capitulated without any agreement, and that the employers had won a total victory over the union. But the confusion did not end there. On Monday morning (July 1), union men showed up for work at the brass shops and insisted on a 30 cents hourly rate per the agreement. They also mentioned the names of the employers who had met secretly with Gersabeck to work out the deal. That set the stage for perhaps the stormiest meeting in the history of the EAD, one which featured accusations of treachery and bad faith.

The front-page story in Sunday’s newspapers presented the brass manufacturers’ version of events—that the strikers had surrendered, capitulated without any agreement, and that the employers had won a total victory over the union. But the confusion did not end there. On Monday morning (July 1), union men showed up for work at the brass shops and insisted on a 30 cents hourly rate per the agreement. They also mentioned the names of the employers who had met secretly with Gersabeck to work out the deal. That set the stage for perhaps the stormiest meeting in the history of the EAD, one which featured accusations of treachery and bad faith.

That evening’s gathering of the Brass Division immediately got down to business. William Fraser now admitted that he had arranged the informal meeting at the Griswold House on Friday afternoon. But he insisted that no negotiations took place and that they had talked with Gersabeck as individuals, not as members of the EAD. All they did, he said, was listen to what the union business agent had to say. They promised Gersabeck nothing, but merely advised him to end the strike.

"What Mr. Fraser says I won't take," countered Howard Anthony, secretary-treasurer of the McRae & Roberts Manufacturing Company, "because I think that committee said something about wages for the reason that Brothers Wagner and Schomer [of the union] said these three gentlemen spoke about the wages at thirty cents." Then, according to the detailed transcript of the meeting, Anthony delivered a nasty jab--"Mr. Wagner's word is as good as Mr. Fraser's. Mr. Fraser has to prove...".jpg?ver=_Dp8mL9vzYQyuUF7H589BA%3d%3d)

Fraser: Fraser will not take the trouble to prove that or anything. Fraser's word is absolutely good with anybody who knows him.

Anthony: You went to [Mayor] Thompson's office and got mixed up there and...

Fraser: I settled your strike which you could not do. You were too arbitrary and had too little brains to do it.

The strike had taken its toll, but neither the public nor the unions ever knew about the breakdown in trust on display among the employers. They certainly were never aware of President Blesch's statement that night—“I feel as if I would like to get out of this institution tonight.”

The EAD held together, but only 29 men, representing 25 firms (just a third of the total membership), attended the annual meeting in February 1908. There, Secretary John Whirl cautiously recounted the previous year’s events, most notably the wave of strikes in 1907. His review of the metal polishers’ strike was relatively brief. Most of his report consisted of a list of legal actions, injunctions, and prosecutions. As for the tail end of the dispute, Whirl claimed that the union simply called off its strike unconditionally on June 28—“thus concluded a nine weeks unsuccessful strike.” Obviously Whirl chose not to reopen recent wounds.

Outgoing EAD President August Blesch, however, broached the sensitive topic. With William Fraser sitting in attendance, Blesch noted that an employers’ association held within it “differences of opinion” due, in part, to the diversity of firms. “Unfortunately,” he observed, “selfishness cuts a large figure in the makeup of humanity, and we sometimes find those in our midst who insist upon advocating a settlement to suit their own particular case regardless of the consequences or serious detriment to the great majority of their fellow members.”