In 1903, Frank Bartlett, the general manager of the Ideal Manufacturing Company, signed the charter of the Employers’ Association of Detroit, making Ideal one of the 73 founding members of the EAD. Within two years, both Bartlett and Ideal would find themselves at the center of one of the most protracted labor battles of the early 1900s.

products.jpg?ver=tjTulfEBvFDHCzC1L-57yQ%3d%3d) Ideal was a typical manufacturing firm in that time before the automobile industry dominated the city’s economy. Henry and George Cope, patternmakers with the Detroit Stove Company, founded Ideal in 1887. They initially produced lawn hose trucks out of a factory located at the southeast corner of Franklin and Dubois streets, close to Detroit’s east riverfront. Several years later, Ideal branched out to make a wide range of plumbing supplies and sanitary specialties, such as sinks, bathtubs and toilets (then commonly known as “water closets”), as well as iron toys.

Ideal was a typical manufacturing firm in that time before the automobile industry dominated the city’s economy. Henry and George Cope, patternmakers with the Detroit Stove Company, founded Ideal in 1887. They initially produced lawn hose trucks out of a factory located at the southeast corner of Franklin and Dubois streets, close to Detroit’s east riverfront. Several years later, Ideal branched out to make a wide range of plumbing supplies and sanitary specialties, such as sinks, bathtubs and toilets (then commonly known as “water closets”), as well as iron toys.

The Cope brothers disappeared from the scene in 1898 when prominent investors stepped in brought about the consolidation of Ideal with the Electric Gas Stove Company. Gas stoves and ranges joined Ideal’s existing mix of products. The new.jpg?ver=aYhdXlS6zjuYqDfqKteNaQ%3d%3d) corporation was owned and led by prominent representatives of Detroit’s stove industry—men with last names like Dwyer, Barbour, Ducharme, and Palms. Jeremiah Dwyer, the president of the Michigan Stove Company, whose biography was most synonymous with the stove industry, was probably the key figure behind the merger. His son, Frank, had been secretary and treasurer of the Electric Gas Stove Company. He now became the secretary of Ideal Manufacturing. James Wright, already wealthy through his three decades of involvement in Michigan’s copper country, served as president.

corporation was owned and led by prominent representatives of Detroit’s stove industry—men with last names like Dwyer, Barbour, Ducharme, and Palms. Jeremiah Dwyer, the president of the Michigan Stove Company, whose biography was most synonymous with the stove industry, was probably the key figure behind the merger. His son, Frank, had been secretary and treasurer of the Electric Gas Stove Company. He now became the secretary of Ideal Manufacturing. James Wright, already wealthy through his three decades of involvement in Michigan’s copper country, served as president.

Detroit’s stove companies, which were among the largest employers in the city, remained aloof from the EAD. Beginning in the early 1890s, they joined in a national collective bargaining agreement between stove manufacturers and the Iron Molders Union that maintained industry stability while enabling the IMU to build one of the most robust trade unions in the country. But employers outside of the stove industry wanted no part of collective bargaining. They formed organizations such as the EAD and opted for the “open shop.” The Ideal Manufacturing Company—despite its connection with leading stove manufacturers—joined their ranks.

At first, Ideal maintained relations with the unions that represented some of their 400-500 employees. The company’s oral agreement with Metal Polishers and Buffers Union No. 1 recognized the 55-hour work week, a 1-to-8 ratio of apprentices to journeymen, and union members’ right to operate polishing machines. It also promised “no discrimination” against union men. Although Ideal was committed to the EAD policy of the open shop, in practice it ran a union shop in its polishing department. It retained the right to employ anybody it chose regardless of their affiliation with organized labor, but in practice all of its thirty or so polishers were union men.

Ideal then changed course. In early January, 1905, polishers returning after a brief layoff discovered that the company had extended the work week to 60 hours. Given slack business conditions, however, they refused to be drawn into an untimely battle. Later that month, the company put Charles Hoffmann, a non-unionist, to work in the polishing room even though a number of union members were still out of work. The polishers left to talk things over with their business agent. When they returned, the found their overalls in a heap outside the factory—an obvious sign that they had been fired or, as they would maintain, “locked out.”

polishing dept.jpg?ver=1HtUyQ38O-CF4LRDgC1y_w%3d%3d) Thus began a costly test of wills lasting twenty months between Ideal’s polishers and union supporters on the one side, and the company and its EAD allies on the other. For the EAD, the struggle was about the right of employers to operate their plants without having to cater to the whims of organized labor—including the right to employ whomever those chose, whether they had a union card or not. For trade unionists, however, it was all about a radical “unholy scheme” by the “wild-eyed agitators” in the EAD, led by its secretary John Whirl, to drive organized labor out of the Detroit. The fact that Whirl had been employed by Ideal’s gas stove department before becoming EAD secretary, and that he had sent the non-union Hoffmann to Ideal in a way that seemed designed to pick a fight, was sufficient evidence of a plot to bust the union.

Thus began a costly test of wills lasting twenty months between Ideal’s polishers and union supporters on the one side, and the company and its EAD allies on the other. For the EAD, the struggle was about the right of employers to operate their plants without having to cater to the whims of organized labor—including the right to employ whomever those chose, whether they had a union card or not. For trade unionists, however, it was all about a radical “unholy scheme” by the “wild-eyed agitators” in the EAD, led by its secretary John Whirl, to drive organized labor out of the Detroit. The fact that Whirl had been employed by Ideal’s gas stove department before becoming EAD secretary, and that he had sent the non-union Hoffmann to Ideal in a way that seemed designed to pick a fight, was sufficient evidence of a plot to bust the union.

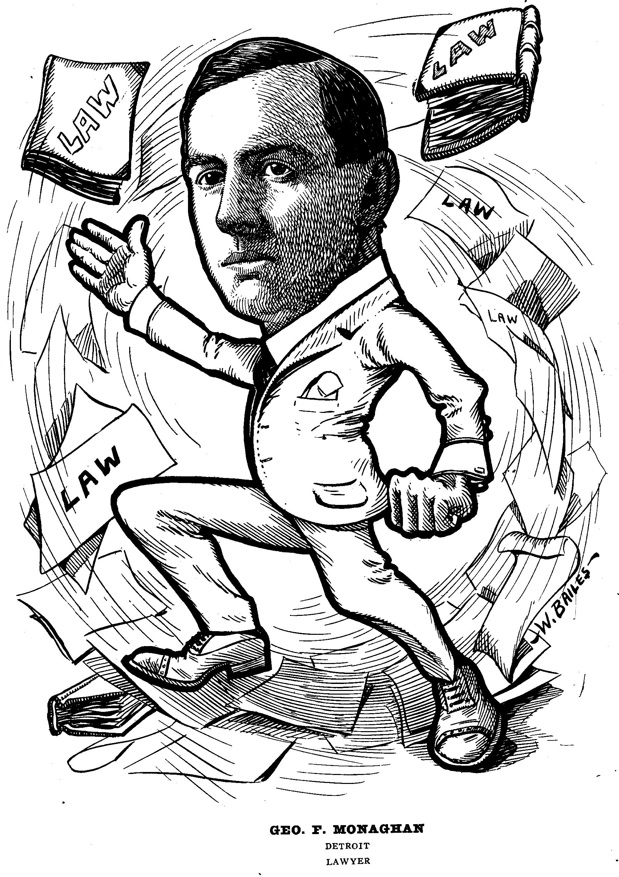

If there was such a plot, then the polishers played right into it. On February 4, a crowd of union supporters picketing at the Ideal plant pounced on Hoffmann as he was leaving work and about to board the Jefferson Avenue streetcar. Police arrested a union polisher and charged him with assault. More importantly, the attack on Hoffmann enabled Ideal, with the aid of the EAD and its ace attorney, George Monaghan, to apply for a court order to restrain the picketers from interfering with Hoffmann and other workers provided to Ideal by the EAD’s labor bureau.

the Ideal plant pounced on Hoffmann as he was leaving work and about to board the Jefferson Avenue streetcar. Police arrested a union polisher and charged him with assault. More importantly, the attack on Hoffmann enabled Ideal, with the aid of the EAD and its ace attorney, George Monaghan, to apply for a court order to restrain the picketers from interfering with Hoffmann and other workers provided to Ideal by the EAD’s labor bureau.

Ordinarily, securing a labor injunction should have been quick and easy. The problem was that the matter came before Joseph Donovan, a Wayne County Circuit Court judge who sympathized with organized labor and counted on labor votes for the upcoming election in April. Initially, Donovan refused to issue an injunction without giving the union a chance to present its case at a hearing. Monaghan appealed to the Michigan Supreme Court, which directed Donovan to issue a temporary injunction against the striking polishers. Donovan complied, but then he ordered a public hearing lasting a week that gave labor a platform to publicly embarrass Ideal, the EAD, and most especially John Whirl.

Seeing the drift of the proceedings, and hoping to find a more congenial judge, Monaghan moved to dismiss the case. Donovan refused. He permitted the opposing attorney an opportunity to make a rousing statement in defense of the union polishers (“There is no more nefarious concern—no greater conspiracy than this Employers’ association. It has but one object: to prevent any union man from obtaining employment in Detroit.”) Donovan would not give Monaghan a chance to respond, and he promptly issued a decree denying the application for a permanent injunction. Outraged, Monaghan’s associate muttered in the direction of the judge, “Your time is short!”

.jpg?ver=crI9jdgPeB4EyQvd8c4vmA%3d%3d) Donovan survived the election contest in early April, but just barely. Shortly after the election, Monaghan managed to secure the long-sought injunction in the court of Judge George Hosmer. The delay of two months, though, had taken its toll on the company. Union supporters had organized a national boycott of Ideal’s products, and their intimidating presence on the streets outside the factory made it difficult for the company to hang on to replacement polishers. But Ideal, backed by the moral and financial weight of the EAD, would not bend. And now that it had its injunction, Detroit police officers began to clear the streets and saloons surrounding the factory of union supporters and, after work, escort strikebreakers to streetcars and sometimes to their homes.

Donovan survived the election contest in early April, but just barely. Shortly after the election, Monaghan managed to secure the long-sought injunction in the court of Judge George Hosmer. The delay of two months, though, had taken its toll on the company. Union supporters had organized a national boycott of Ideal’s products, and their intimidating presence on the streets outside the factory made it difficult for the company to hang on to replacement polishers. But Ideal, backed by the moral and financial weight of the EAD, would not bend. And now that it had its injunction, Detroit police officers began to clear the streets and saloons surrounding the factory of union supporters and, after work, escort strikebreakers to streetcars and sometimes to their homes.

By the winter of 1905-06, it appeared to most observers that the metal polishers’ dispute at Ideal was over. In late March, however, crowds again assembled outside the plant at the end of the workday—apparently in retaliation for the EAD’s support of the ouster of union polishers by the Burroughs Adding Machine Company.

A sharp escalation occurred in May, and in early June confrontations took place around the Ideal factory between large crowds of workers and police officers escorting strikebreakers. Despite the injunction and police protection, frightened non-union men quit working for Ideal. With the streets seemingly in the hands of a riotous mob, the Detroit Journal asked, “Is Detroit’s Government Impotent?” The chastisement led police to fight back aggressively with “no loitering” orders and with clubs, prompting a stern warning from Ben Stouder, the union business agent: “If the police start this clubbing, there’ll be a thousand men down here at Ideal. They won’t stand for it. No man will stand for it in free America. The union men don’t come here for fights, but clubbing starts riots.”

.jpg?ver=6xJM6r21VxD1d0sAhwlNFA%3d%3d) Just as it appeared that the police had retaken control of the streets, Detroit’s trade unionists provoked a decisive confrontation. On the morning of August 2, 1906, a crowd of some 500 workers (some armed with clubs, stones, and bricks) descended on surprised officers and strikebreakers on their way to work at Ideal. Another clash took place at the end of the work day. Police arrested eighteen men for

Just as it appeared that the police had retaken control of the streets, Detroit’s trade unionists provoked a decisive confrontation. On the morning of August 2, 1906, a crowd of some 500 workers (some armed with clubs, stones, and bricks) descended on surprised officers and strikebreakers on their way to work at Ideal. Another clash took place at the end of the work day. Police arrested eighteen men for.jpg?ver=LEFN8mnVKbQDJbqcGo430g%3d%3d) disturbing the peace. The next day nearly one hundred officers showed up to pacify the area around the factory.

disturbing the peace. The next day nearly one hundred officers showed up to pacify the area around the factory.

Unnerved, Ideal closed for a week as its directors decided what to do next. They picked up rumors that organized labor planned to have 8,000 men march past the plant when it reopened. Word leaked that the company was considering leaving Detroit due to the labor troubles. This was all too much for the EAD to take. On the evening of August 8, EAD members came together at a special meeting and pledged to terminate every union member in their employ (about 4,000 men) if labor continued to molest the Ideal company. What had been a protracted labor struggle involving a single EAD member and a local union now broadened into a general showdown between all EAD members and organized labor.

By the end of the month, representatives for Ideal and the Metal Polishers’ Union began meeting to find a way out of the crisis. On September 7, the Detroit News, declaring that “the dove of peace will once more hover over Franklin Street,” reported that a settlement was near in the long dispute..jpg?ver=44wMI2wna9jiU9ocfnLQLA%3d%3d)

Neither side revealed the terms of the settlement, but no doubt there was a compromise that brought an end to Ideal’s ordeal. Ideal must have retained the principle of the open shop. In exchange, the company likely conceded the 55-hour work week, hinted that it would return to operating a union shop, and agreed that no employee would have to first pass through the EAD’s labor bureau. Several personnel changes at Ideal cemented these developments. In early 1907, Jeremiah Dwyer’s son, James, became the company’s vice president. Later in the year, he also replaced Frank Bartlett as general manager. It seems that Bartlett, who had represented Ideal at meetings of the EAD, paid the price for the costly labor war.

Not one of the EAD’s officers mentioned the conclusion of the Ideal strike at the annual meeting in February, 1907. But there was one more stinging blow to come. In July, the Michigan Supreme Court upheld the ten-day jail sentence handed to Martin Ludwig, the president of the Polishers’ Union in Detroit, for violating the injunction the previous year. Two weeks later, three of Ideal’s officers wrote the Wayne County Circuit Court and asked it not to enforce the sentence against Ludwig. Having made peace with the union, the company clearly did not want to stir up trouble again.

The EAD, which had contributed thousands of dollars to Ideal’s defense, was stunned by what must have felt like an act of desertion. Labor, on the other hand, rejoiced. “Since the troubles of last year were amicably settled,” noted Detroit’s labor newspaper, “this company has placed itself right in line as a union shop [and] in the front rank as a friend of organized labor.”

The photographs of Ideal Manufacturing Company’s showroom and polishing department are provided courtesy of Fondazione MAST, Bologna, Italy.