In the summer of 1983, I had the opportunity to sit down and record an interview with Employers’ Association of Detroit Vice-President Kenneth Porter the year before his retirement. Porter, who had been with the EAD since the early 1950s, was immensely knowledgeable about the history of the association and labor relations in Detroit more generally. I vividly recall his description of the EAD in the period after its founding in late 1902:

“You know, in the early days, we did have war chests, we did bring in strikebreakers, we fought with tools that were accepted at the time, both by the unions and management. It was unsophisticated street-fighting, that’s what it was. We were the money-bags keepers to pay off the fighters.”

Indeed, the EAD in essence was a fighting organization. In taking on various trade unions, the EAD made use of a host of methods that were both common and legal at the time. They included recruiting strikebreakers (called “scabs” or “rats” by trade unionists) from both near and far; seeking court-issued labor injunctions against strikers and their supporters; and making use of informants or spies who passed on information about union plans and members.

As Porter suggested, fighting the unions was costly, both for struck employers (who might suffer lost production and sales) and for the association, which covered things such as legal expenses and the costs related to the recruitment of strikebreakers. The fundamental logic behind establishing an employers’ association was to pool financial resources (members’ dues) in order to prosecute the battles against the trade unions.

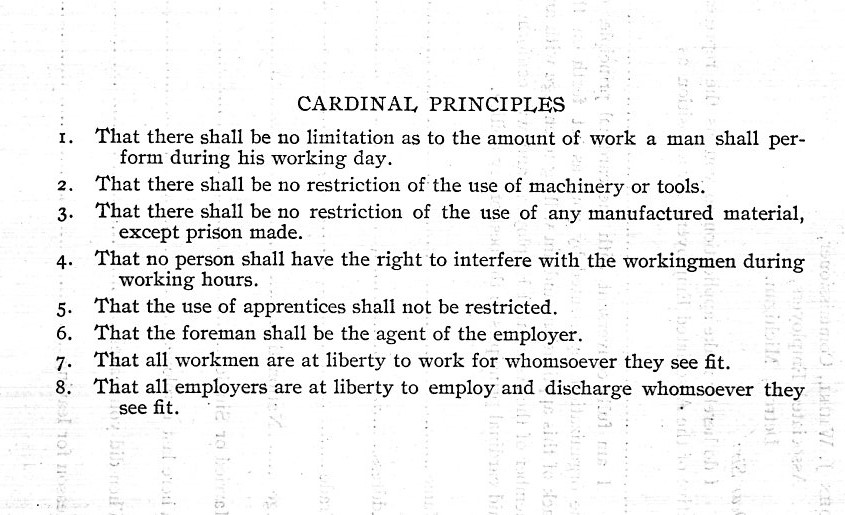

From the start, the EAD declared its adherence to the principle of the “Open Shop”—the notion that employers should hire workers irrespective of their membership or non-membership in a union. It also adopted a set of “Cardinal Principles” which, in practical terms, undermined the rules and practices that sustained trade union power in labor markets and in work places.

Despite its cherished principles, the EAD did not immediately launch a crusade against organized labor. For one thing, the timing wasn’t right. In 1903, companies were busy filling orders and workers were hard to find. If employers had learned one thing over the years it was that the worst time to get into labor troubles was when the labor market was tight and the unions held a favorable advantage.

The EAD and its members also operated with a sense of caution. While only 6.2% of Detroit’s labor force belonged to unions in 1901, union membership was concentrated in certain sectors .jpg?ver=B3wJ0iGUrEp7iZPAXcvCig%3d%3d) and especially among skilled workers. Union density among industrial workers was about 15%, and it reached as high as 37% among those working in the metal trades. Every iron molder working in the foundries of the city’s renown stove companies belonged to Iron Molders Union No 31. It was the strongest union in the city and it lent its support to other workers and unions. Overwhelming percentages of machinists, brass polishers and buffers, as well as printers and building trades workers belonged to their respective unions.

and especially among skilled workers. Union density among industrial workers was about 15%, and it reached as high as 37% among those working in the metal trades. Every iron molder working in the foundries of the city’s renown stove companies belonged to Iron Molders Union No 31. It was the strongest union in the city and it lent its support to other workers and unions. Overwhelming percentages of machinists, brass polishers and buffers, as well as printers and building trades workers belonged to their respective unions.

At the dawn of the 20th century, union strength in Detroit was entrenched and growing. Between 1900 and 1903, the number of union members in Detroit grew from about 8,000 to 14,000. Considering that the EAD had 68 member firms at the time of its first annual meeting in February 1904, and together they employed some 11,000 skilled and unskilled workers, it was clear that organized labor in Detroit was a force that deserved cautious respect from employers.

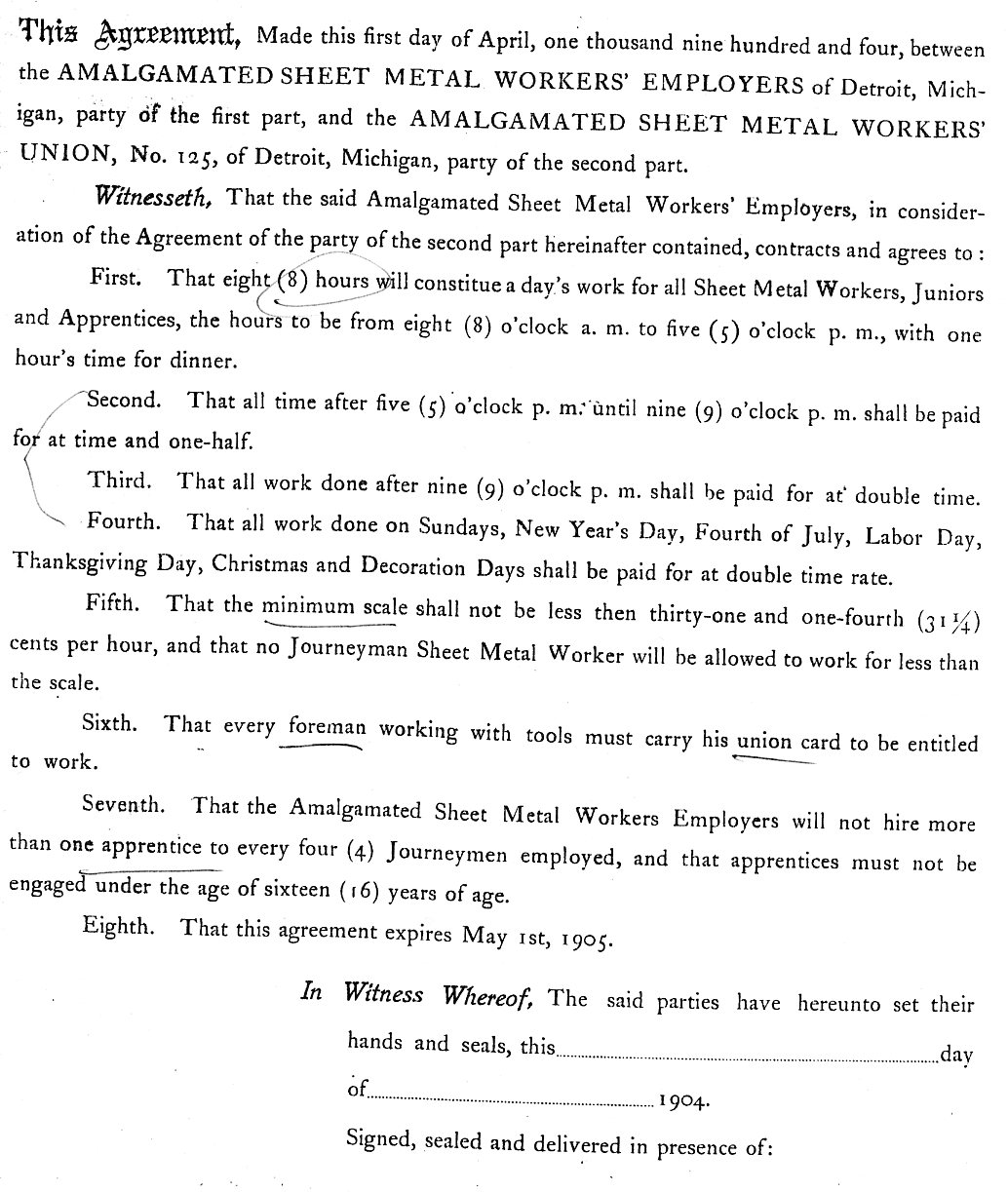

For a while, the EAD and its members continued to recognize and meet with representatives of union shop committees and local union business agents. They also continued to renew agreements that set the terms and conditions of employment, such as the minimum daily wage, the length of the work day, overtime and holiday pay, the ratio of apprentices to journeymen, and the right of union members to operate labor-saving machinery. Some of these agreements were made orally, but others were written – such as this one-page agreement in 1904 between Sheet Metal Workers Union No. 125 and the Sheet Metal Workers Employers of Detroit, which was not affiliated with the EAD:

In May 1903, the EAD’s Brass Division met with the committee representing the unions in the brass industry and renewed the annual agreement that provided a 5% wage increase and recognized the 55-hour work week. A year later, despite a business downturn which swung the advantage to the employers, the Brass Division again renewed the agreement, but only on a month-by-month basis.

In early September, 1904, with the economy still soft, members of the Brass Division met and decided that the time had come to change the terms of employment. They disagreed, however, about what to do and how to go about it. Some brass manufacturers wanted to impose wage cuts, but others opposed it. Some saw an opportunity to increase the work week to 60 hours, but others warned against it. They also debated whether to sever all relations with the unions and put an end to collective agreements with labor.

A couple of pragmatic employers spoke to the advantages of continuing to deal with the representatives of organized labor. “These people control a certain number of men,” explained Stephen Johnson of the Penberthy Injector Company and also Vice President of the EAD. He pointed out that “[we] have had a year and a half of peace because we have had an understanding with them. I don't believe we ought to ignore these people. We treated them as gentlemen and all the talks we have had have ended in some good.”

Most brass manufacturers, however, agreed with Dougald Roberts of the McRae & Roberts Manufacturing Company, who proposed terminating the agreement at the earliest opportunity, presenting workers with a new policy on wages and hours, and threatening to replace them if they did not accept the new terms of employment. Roberts insisted, however, that employers had “to be very reasonable and not go to extremes” to avoid provoking a massive confrontation with the unions.

EAD Secretary John Whirl duly informed the brass unions that the Brass Division would no longer honor the agreement, effective October 9, 1904. Following further meetings throughout October, employers hammered out an agreement among themselves to impose a small reduction in wages.

While employers were preoccupied with the approaching wage reduction, a dispute erupted between the Clayton & Lambert Manufacturing Company and Metal Polishers and Buffers Union No. 1. The trouble brought the EAD and the city's brass unions to the verge of all-out war.

Clayton & Lambert started in Ypsilanti in the mid-1880s. Looking to expand, it relocated to Detroit in 1899. At its factory located on the southeast corner of Beaubien and Trombly, the company made an assortment of brass products connected to the plumbing industry, notably top-selling blow torches and fire pots for melting lead. The trouble began in early November when laid off metal polishers learned that they could return to work, but at lower pay. Seeing the company’s act as part of a nefarious plot by John Whirl and the EAD, the union’s business agent informed the

Clayton & Lambert started in Ypsilanti in the mid-1880s. Looking to expand, it relocated to Detroit in 1899. At its factory located on the southeast corner of Beaubien and Trombly, the company made an assortment of brass products connected to the plumbing industry, notably top-selling blow torches and fire pots for melting lead. The trouble began in early November when laid off metal polishers learned that they could return to work, but at lower pay. Seeing the company’s act as part of a nefarious plot by John Whirl and the EAD, the union’s business agent informed the .jpg?ver=aSD5Tqufwb9hMmkisUI2MQ%3d%3d) management that no union member would work in its polishing department until it restored a fair scale.

management that no union member would work in its polishing department until it restored a fair scale.

The EAD saw the labor embargo against one of its members as an unwarranted act of union aggression that called for a collective response. On November 15, Whirl wrote to every polisher and buffer employed in the shops of EAD members--some 300 workers--and informed them that they would be locked out unless the labor boycott against Clayton & Lambert was lifted by Monday, November 28.

Just as the crisis reached the flash point, both sides backed down. Nobody revealed how the union and the management at Clayton & Lambert resolved their differences. Nevertheless, the episode showed how a labor dispute could quickly escalate to embroil a whole industry. It also dramatically showed the determination of the EAD to stick up for one of its member firms.